The DFA’s public consultation exposes Europe’s survey sore spots

The DFA consultation is structured in a traditionally biased way: supporters of more regulation can justify their view, while dissenters cannot. To uphold Better Regulation principles, the Commission should adopt a neutral, balanced survey design.

With less than two weeks remaining in the European Commission’s Call for Evidence and Public Consultation on the Digital Fairness Act (DFA), European citizens, companies, various organisations (and many, many gamers) are submitting their positions via the Have Your Say portal.

The supporting exercise for Call for Evidence - a Public Consultation for the Digital Fairness Act - is structured in a traditionally biased way, where only those who agree with the need for more regulation are given options to explain themselves.

This is concerning because the future impact assessment will take into account the Consultation results. If those who disagree do not have a fact- and argument-based way to explain themselves, the impact assessment will only reflect part of Europeans’ thoughts.

This approach is neither new nor exclusive to the Digital Fairness Act; however, to truly adhere to Better Regulation principles, as well as ensure fair and open stakeholder involvement in decision-making, changes must be made.

No options for the opposition to explain themselves

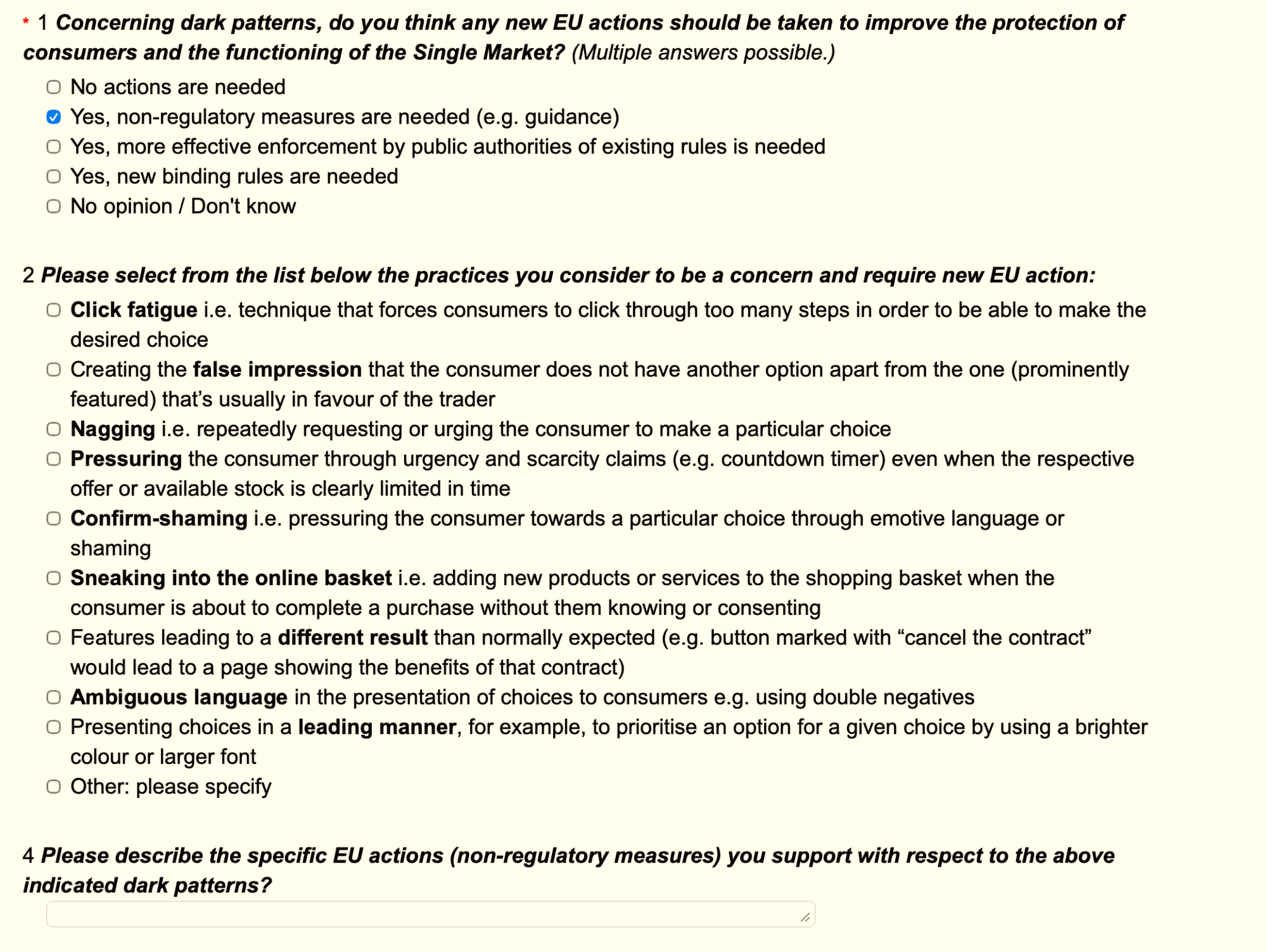

Picture 1 below shows that only respondents who support the European Commission’s ambition for the Digital Fairness Act are given multiple-choice options to explain their view, along with an open-ended field for additional feedback.

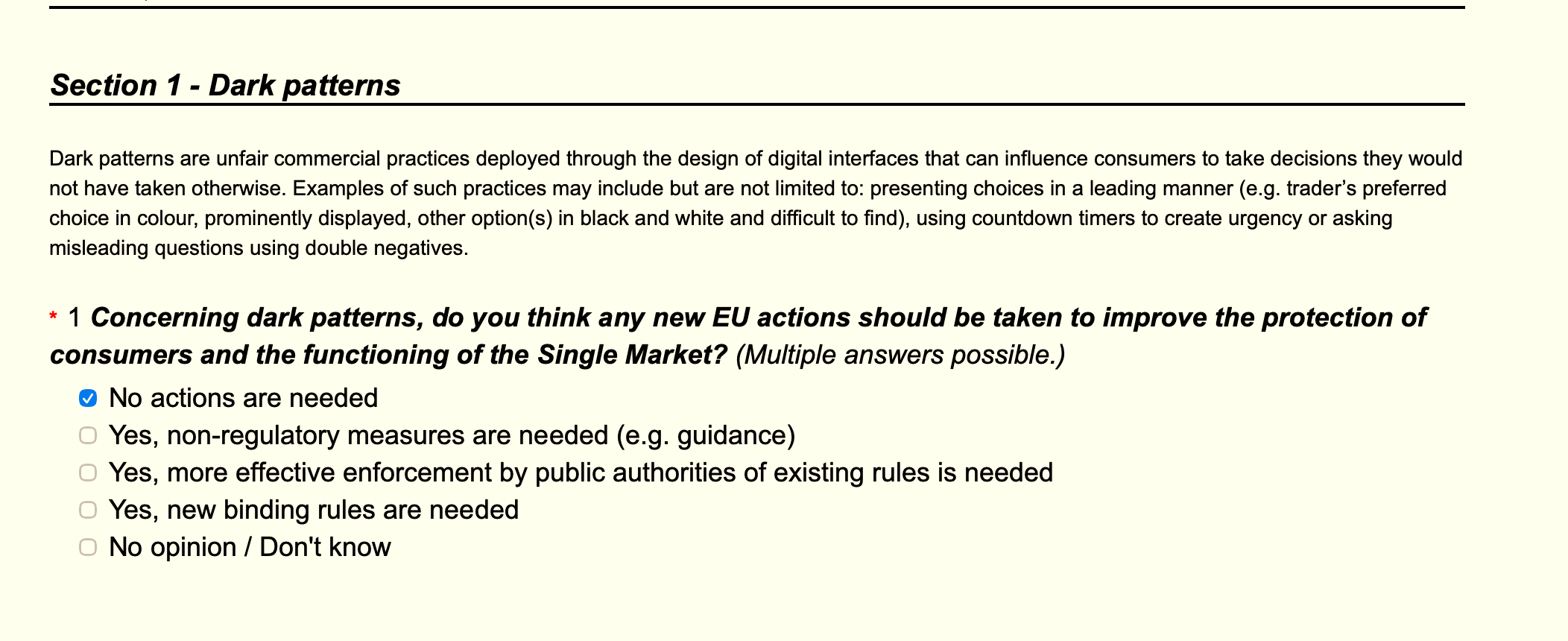

By contrast, those who do not believe a new action is needed (see Picture 2) are limited to a single option—“No actions are needed”—with no opportunity to explain their position, either via additional Commission-provided prompts or even a free-text field to present fact- and argument-based reasoning.

The European Commission should set a high(er) bar for methodology and fairness

First-year students in any reputable political science program are taught that survey questions should be neutral, avoiding loaded or double-barreled items, with key terms defined and balanced framing that allows different opinions to be expressed.

Unfortunately, these principles are often not upheld in the EU by both public and private organisations. Biased surveys distort the very purpose of these exercises: they should be inclusive, provide space for alternative opinions, and reflect the diversity of European views; instead, they steer results toward a predetermined outcome. It may be practical, but it is unfair and does not reflect the principles of evidence-based policymaking, which must include differing opinions.

The European Commission has the manpower and resources to set a higher bar for consultations and surveys—standards that could then trickle down and shape the practices of other organisations.