GPAI Code of Practice: American-European trade negotiations, ‘hack clause’, lack of Member State involvement

As the EU awaits the third draft of the General Purpose AI Code of Practice, debates over its scope and details continue. We explore its impact on U.S.-EU trade negotiations, its role as a 'hack clause,' and the lack of attention from Member States.

As the EU is awaiting for the third draft of the General Purpose AI Code of Practice, the debates on the scope and details continue.

One group of people, primarily representing market-oriented politicians and tech companies, has raised concerns about the broad scope of the Code of Pracice, arguing that it deviates from the original agreements within the AI Act framework and creates negative precedents for the future.

Another group, consisting of authors (mainly), has voiced concerns about copyright and even criticized the exemptions for SMEs—a European protectionist approach aimed at protecting homegrown businesses from the potential negative impact of the GPAI Code of Conduct on innovation.

With no compromise in sight, the European Commission has decided to reevaluate the feedback received. The third draft of the GPAI Code of Practice was scheduled for release on February 17, 2025, but according to Euronews, it may be delayed by a month.

The AI Board is meeting tomorrow, so we can hopefully expect updates on the third draft very soon. The initial idea was to have the Code of Practice adopted by May, so that companies have time to adapt before it coming into force in August 2025.

The tricky part #1: American - European trade negotiations

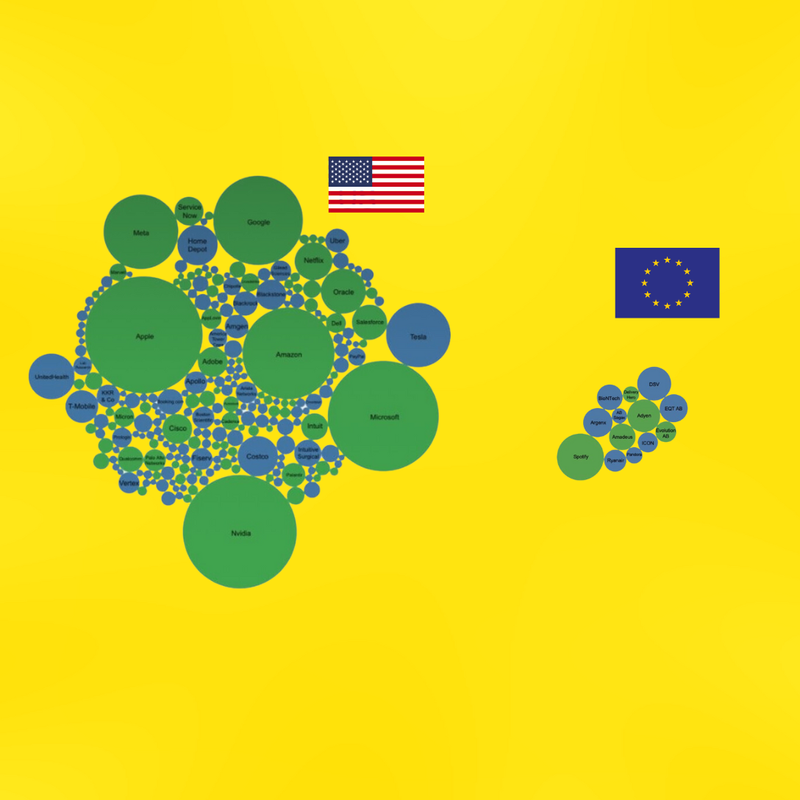

Despite heated rhetoric on platforms like X, EU officials have yet to decide whether—or how—to respond to Donald Trump’s statement on “Unfair exploitation of American innovation” which criticized the effect of European tech regulations on American tech companies. While the main focus within the statement is on digital service taxes, DSA and DMA, it is likely that the GPAI Code of Practice (or related rules) will become part of the discussion too.

While some Members of the European Parliament have firmly opposed any concessions on the EU’s tech policies, the European Commission will inevitably have to engage in negotiations, as the U.S. administration has made tech regulation a priority area for reconsideration.

Moreover, some in Europe see this as an opportunity to scale back what they view as excessive regulation.

The tricky part #2: the GPAI Code of Conduct as a ‘hack clause’ within the AI Act

European officials have long pushed for having a s0-called "hack clause" in regulatory frameworks, giving them room to adjust as technology evolves. It is absolutely true that the European continental legal system has its fair share of limits and the Acts/Directives/Regulations tend to be somewhat outdated by the time they are adopted, let alone implemented.

In this case, the GPAI Code of Conduct effectively acts as that "hack clause"—which makes sense from an operational perspective but doesn’t from an innovator or consumer perspective, as the reporting requirements are broader than those within the AI Act, which clashes with the very principle of regulatory certainty, leaving businesses in a state of limbo.

This also sets a major precedent for future policies—where political agreements with sufficient political attention can effectively be bypassed through clauses like this.

AI Act’s Article 57 is clear about the fact the Code of Conduct’s role is to be reviewed and adapted as needed:

a) he means to ensure that the information referred to in Article 53(1), points (a) and (b), is kept up to date in light of market and technological developments”

“8. The AI Office shall, as appropriate, also encourage and facilitate the review and adaptation of the codes of practice, in particular in light of emerging standards. The AI Office shall assist in the assessment of available standards.”

Moreover, the Commission leaves itself the option to require participants to “report regularly". A broad set of reporting obligations, combined with ad hoc requests, typically leads to high compliance costs that inevitably get passed on to consumers. Europeans have already experienced delays in accessing AI functionalities and innovations available elsewhere:

5. The AI Office shall aim to ensure that participants to the codes of practice report regularly to the AI Office on the implementation of the commitments and the measures taken and their outcomes, including as measured against the key performance indicators as appropriate. Key performance indicators and reporting commitments shall reflect differences in size and capacity between various participants.

Lastly, while the GPAI Code of Conduct is technically a voluntary mechanism—meaning tech companies must opt in—it comes with a mix of voluntary commitments and ad hoc regulatory oversight set to begin in August 2025. However, this doesn’t mean the European Commission won’t eventually codify its scope in some form, effectively making it mandatory. The Commission’s own website states:

“Based on Article 56(8) AI Act, “the AI Office shall, as appropriate, also encourage and facilitate the review and adaptation of the codes of practice, in particular in light of emerging standards”. The third draft of the Code of Practice includes a suggested mechanism for its review and updating.”

The tricky part #3: lack of awareness among Member States

One of the key roles in shaping (and updating) AI policy—alongside the Commission and the AI Office—has been assigned to the AI Board, which is composed of representatives from EU Member States.

However, given the workload national governments already face—particularly in countries with smaller bureaucracies—it’s likely that the GPAI Code of Conduct won’t receive the attention it deserves.

With multiple rounds of consultations already conducted and the Code’s broad scope, there’s a real risk that its implementation will be treated as a secondary priority.

“The AI Board includes representatives from each EU Member State and is supported by the AI Office within the European Commission, which serves as the Board's Secretariat. It is chaired by one of the EU Member States. The Board plays a crucial role in the governance framework set out by the AI Act, ensuring the effective implementation of the AI Act across the European Union. The European Data Protection Supervisor, and EEA-EFTA countries, participate in Board meetings as observers.

<...>

A key responsibility of the AI Board is to provide advice and assistance with implementing the AI Act, including discussing guidelines, draft delegated and implementing acts. These are essential to make sure that the AI Act’s provisions are easy to understand, implement and enforce.”