A dangerous new proposal for Chat Control

Denmark’s EU Presidency has released a new, 203-page draft for Chat Control. Despite diplomatic tweaks, vague “risk mitigation” obligations could still require scanning of private messages, including those encrypted.

The Danish Presidency of the Council of the European Union has published a new 203-page text on Chat Control, following discussions among EU Member State representatives in Brussels. Some diplomatic tweaks have been made, but the vague “risk mitigation” language and loopholes that would force the scanning of private communications indicate that the proposal hasn’t moved far from the original plan.

The future outlook isn’t brighter either: if the Chat Control proposal is not adopted by the end of the Danish Presidency in December, the file will be passed to the upcoming Cypriot Presidency, which also supports Chat Control.

In characteristically European fashion, the new text speaks of “targeted, carefully balanced, and proportionate” actions, but offers little substance to support that. Vague definitions and loopholes in the new text still leave room for the forced scanning of private communications in practice.

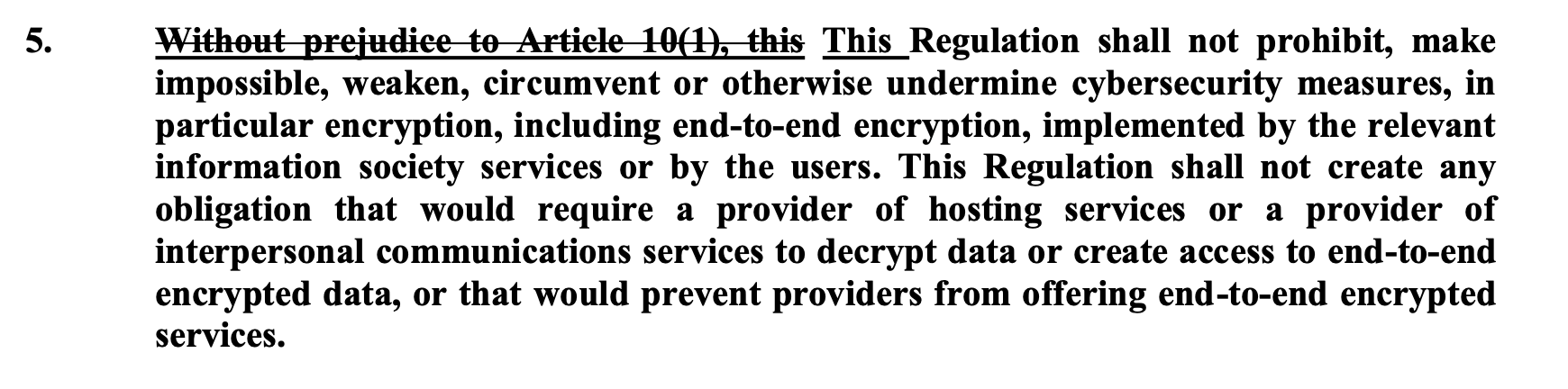

The new proposal tried to address the criticism that Chat Control harms Europeans’ privacy and end-to-end encryption by stating that the regulation should not weaken encryption (Article 1(5) (See Picture 1), however, the de facto situation remains unchanged - the obligations would practically have to extend to end-to-end encrypted communication.

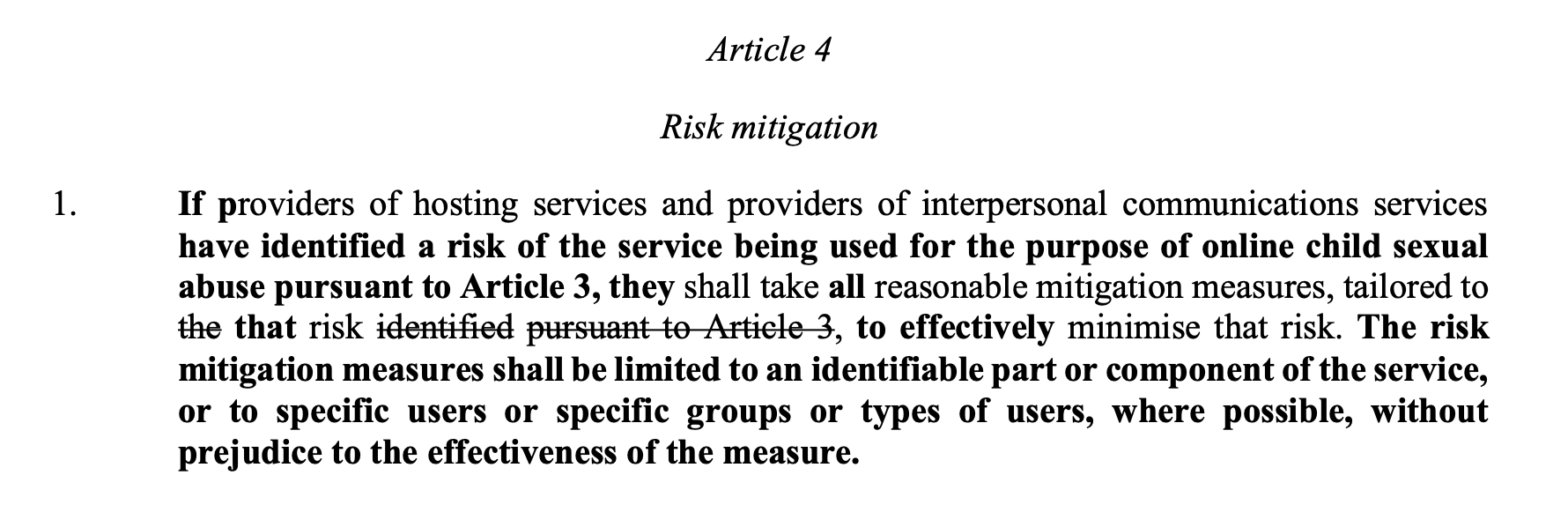

Former MEP Patrick Breyer notes that a loophole in the new draft’s Article 4 obliges service providers to take “all appropriate risk mitigation measures”. What does that mean in practice? The vagueness of this requirement effectively allows authorities to compel providers to scan all private messages, and there is no way to do so without scanning end-to-end encrypted services.

The text also imposes extensive obligations on service providers to implement age-verification features to protect minors. What would that mean in practice if introduced?

As we’ve written before, to do that effectively, providers would need to verify the identity of every user. This would undermine the freedom of communication between whistleblowers and journalists, as well as other vulnerable people, and could prevent children and teenagers from downloading a wide range of apps.